|

Abstract Booklet E-Book Format Contents Causative Constructions in Magahi Alok, Deepak Ananda, M. G. Lalith Crosslinguistic Semantic and

Translation Priming in Normal Bilingual Individuals across Gender Arya, Pravesh, Akanksha Gupta,

Brajesh Priyadarshi Attar, Mahan & S.S.Chopra Phonological, Grammatical and Lexical

Interference in Adult Multilingual Subjects Avanthi. N & Abhishek. B.P Baraik, Sunil Barodawala, Asma I. & T. Sree

Ganesh Naming Deficits in Bilingual Aphasia Batra, Ridhima & Pallavi Malik

& Shyamala K.C Voicing patterns in Indian English Bhattacharya, Pratibha Resultative and Stative in Bangla: How

different? Bhattacharya, Shiladitya Cardoso, Hugo Canelas Revised Receptive Expressive Emergent

Language Scales for Kannada Speaking Children Deepa M.S., Madhu K, Harshan K

& Suhas Devika.M.R, Navitha U & Dr.

Sapna N. ELDP Data Collection: Some Baram Experiences Dhakal, Dubi Nanda, TR Kansakar, YP Yadava, KP Chalise, BR Prasain, Krishna Paudel Jadhav, Arvind & Nick Ward Lexical Organization in Malayalam-English

Bilinguals Joy, Sweety, Meera Priya.C.S,

Aiswarya Anand & Jayashree Shanbal Temporality in Bengali: A Syntacto-Semantic

Framework Karmakar, Samir Gilchrist's 'A Grammar of Hindoostanee

Language': Some Colonial and Contemporary Imprints Kumar, Santosh The Biolinguistic Diversity Index of

India Kumar, Ritesh Kumar, Shailendra & Neha

Vashistha Gitanjali: A Study in Lyrical Patterns (Syntax,

Diction & Rhythm) Kusum Case marking in Asamiya in comparison with Bangla Lahiri, Bornini The Semantics of Classifiers in some Indian

Languages Lahiri, Bornini, Ritesh Kumar,

Sudhanshu Shekhar & Atanu Saha Word Retrieval Abilities in Bilingual

Geriatrics Maitreyee, Ramya & Ridhima

Batra Implementation of Transfer Grammar in

Telugu Hindi Machine Translation System Mala, Christopher Automatic

Extraction and Incorporation of Purpose Data into Purposenet Mayee, P. Kiran Developing a Morphological Analyzer for

Kashmiri Mehdi, Nazima, Aadil A. Laway

& Feroz Ahmad Lone Second Language (L2) Vocabulary Acquisition in

Icelandic Contexts Misirili, Nilufer Pronominal Binding in Hindi-Urdu vis-à-vis

Bangla Mukherjee, Aparna Naidu, Y. Viswanatha Naresh D. Nash, Joshua Reflexivity and Causation: A Study of the

Vector ghe (TAKE) in Marathi Ozarkar, Renuka Pande, Hemlata Cross Language Variants in Linguistic

Deficits in Dementia of Alzheimers Type (DAT) Individuals Ravi, Sunil Kumar Positional Faithfulness for Weak

Positions Sanyal, Paroma Main Verb and Light Verb in Bangla: Only Apparent

Synonymy? Saurov, Syed Role of Working Memory in Typically Developing

Childrens Complex Sentence Comprehension Shwetha M.P, Deepthi M., Trupthi

T.& Deepa M.S. Beyond Honorificity: Analysis of Hindi

jii Thakur, Gayetri Fastmapping Skills in the Developing Lexicon in

Kannada Speaking Children Trupthi T., Deepthi M., Shwetha

M.P., & Deepa M.S. & Nikhil Mathur A Knowledge-Rich Computational

Analysis of Marathi Derived Forms Vaidya, Ashwini Communication through Secret Language:

A Case Study Based on Parayas Secret Language Vamanan, Dileep Vijay, Dharurkar Chinmay Book of Abstracts Causative Constructions in Magahi

Deepak

Alok Deptt. of Linguistics, BHU, Varanasi E.

Mail: deepak113alok@yahoo.co.in Causative constructions play a

significant role in different areas of the grammar of a language. Some languages

exhibit morphological causativization whereas some languages undergo complex

syntactic processes to realize causative constructions. Magahi, like major

Indic languages such as Hindi and Bangla, show morphological marking to

realize causativization of a verb (haT move -> haTaa

move -> haTbaa cause (somebody) to move something).

Causativization of verb has significant syntactic and semantic consequences

and scholars have worked on this topic for various Indian languages (Kachru

1973, 1976, Amritavalli 2001, etc). In this paper, I attempt to examine the

process of causativization in Magahi. I look at the morphological processes

involved in causativising a verb and also the properties of various arguments

in causative constructions in Magahi. The most common morphological marker

for causative is a suffix baa (dauR run -> dauR-baa

to cause to run) but there are also variations (dauR run -> dauRaa

to cause to run). I attempt to show that this variation can be semantically

explained. In the first case, the causer is close/direct whereas in the

latter case, the causer is distant/indirect. In the second case, there is

also a scope for an extra argument whereas in the first one there is a single

causer (1). This distinction is not available to all the verbs. For instance,

in the case of gir fall -> giraa drop/cause to fall/fell

-> girbaa make (s.b) cause (s.b) fall. Wh-Questions in Sinhala

M.

G. Lalith Ananda Centre for Linguistics, SLL&CS, Jawaharlal Nehru

University, New Delhi E.

Mail: mlalithananda@yahoo.com This paper aims to discuss

WH-Question phenomena of Sinhala in Root, Embedded, and Yes/No questions with

special emphasis on certain syntactic and morpho-syntactic operations that

seem to interact with a number of other modules of grammar. In particular, it

will examine the role of verb morphology in WH questions, types of movement,

the relation between WH and Focus, and D-Linked WH phrases and will also

attempt to integrate the Sinhala WH-facts in to the cross-linguistic typology

of WH phenomena. As shown in example (1), WH in Sinhala displays the

following characteristics of whose configurations lead to different syntactic

and semantic representations. (soodanava wash, soodanna

to wash, seeduwa washed, seeduwE E- form) 1) Ravi

mokak da seeduwE? What did ·

Question

word remains in-situ ·

Question

word is followed by Q-morpheme da ·

E-marking

of the verb The paper will argue that Sinhala WH-facts

motivate both overt and covert movement, overt movement being restricted to

partial WH movement in the embedded periphery. In particular, it will be

shown that the relevant heads for WH operations in Sinhala are FORCE,

INT(ERROGATIVE), and FINITENESS that constitute the left periphery as

proposed by Cinque (1997, 1999). It

will also be argued that the E-morphology of the verb interacts with

Pragmatics making a distinction between De Re/De Dicto reading thereby

showing more evidence for Syntax-Pragmatics interface. A significant

generalization that surfaces in the study is that the left periphery of South

Asian Languages is more articulate than had been once assumed as shown by

Whin situ, a disjunctive particle, and a Quotative that can occupy the same

clause. Another generalization is that Sinhala WH always has covert movement

just like any other SOV language like Chinese or Japanese. Crosslinguistic Semantic and Translation Priming in Normal

Bilingual Individuals across Gender

Pravesh

Arya, Akanksha Gupta, & Brajesh Priyadarshi All India Institute of Speech and Hearing, Mysore E. Mail: pravesh_arya_here@yahoo.co.in;

akanksha041184@yahoo.co.in; brijesh_aiish@gmail.com INTRODUCTION The terms bilingual is used to describe comparable

situations in which two languages are involved. A bilingual person, in

the broadest definition, is one who can communicate in more than one

language, be it actively (through speaking and writing) or passively (through

listening and reading). Potter, Von Eckardt and Feldman (1984)

proposed two models i.e. Word association model and Concept mediation model,

to understand the nature of a bilinguals semantic memory, where former model

states that lexical representations from language 1 are directly linked to

the conceptual system whereas, the words of language 2 are connected only to

language 1 and have no direct connections to the conceptual system and later

model suggests that representations of the two languages are not directly

connected and operate as separate systems that are directly connected to the

amodal conceptual system. To understand whether a bilinguals semantic

representations are linked across the two languages researchers have

frequently used the semantic priming method. Semantic priming is based on the

premise that , upon presentation of a word, the corresponding concept and

associated conceptual nodes are automatically accessed. Several

studies have examined the nature of crosslinguistic and semantic priming in

normal bilingual adults. Some investigators used bilinguals who acquired L2

sometime between childhood and adulthood (Chen & Ng,1989; Kirshner et al;

1984) while others studied those who learned L2 during adulthood (Frenck and

Pynte,1987) As for translational priming in early

bilinguals, all experiments reviewed reported significant transition priming

in the L1-L2 direction while only one-third found significant translation

priming in the L2-L1 direction. The trends are similar in the late

bilinguals, i.e robust L1-L2 priming and less consistent L2-L1 priming.

Overall, the translation priming data suggest that L1-L2 priming is very

robust and that early and late bilingual process L1 primes in a similar way

but what differentiates the group is performance in processing L2 primes. Results of a recent study done

by Kiran,

Swathi; Lebel, Keith R.(2007) on Semantic and Translation Priming in

English Spanish normal bilingual individuals and bilingual aphasics ,showed

that there was no difference

between translation and semantic priming effects for normal group and two

participants among 4 participants

demonstrated greater priming from Spanish to English whereas two

participants demonstrated the opposite effect. AIM : Aim of the study is to examine crosslinguistic semantic

and translation priming during lexical decision task in Hindi-Kannada

speaking normal adult male and female bilingual individuals. The present study is aimed to answer the following

research questions that are-

METHOD Participants A total of 24 Hindi-Kannada speaking normal bilingual

individuals (12 male and 12 female; age range- 18 to 30 years) will be

participated in the study.Participants

will be selected on the criteria of having normal or

corrected-to-normal vision and no known reading or learning disorder. All

participants will be having no neurological and medical histories. Tools All testing will be

done on IBM-compatible notebook computer with an Intel-Pentium processor,

running Windows XP and loaded with DMDX software(foster & foster,1999). Procedure Two prime target relationship will be developed :

semantically related pairs and translation pairs. Twenty critical words list will be prepared for

all critical word pairs. Each word will be paired with a semantically related

word to form 20 semantically related SR ,for e.g cat (billi in hindi)- dog (nai

in kannada ) word pairs. All word pairs will

be contained one Hindi and one Kannada word. Further, one half (10) of the

word pairs will be containing a Hindi prime and a Kannada target (H-K) and

the other half will be containing a Kannada prime and a Hindi target (K-H) to balance language direction. To

examine translation priming, each of the 20 target words will be paired with

its corresponding translation TR for e.g cat

(billiin hindi )- cat(

beku

in kannada) , one half the word list

will be Hindi-Kannada and other half Kannada Hindi. Using the stimuli discussed above,different versions of

the testing will be created. Within each version, each participant will be shown

40 word pairs presenting in random order : 10 crosslinguistic semantically

related (SR), 10 crosslinguistic

unrelated (SU) 10 translation pairs (TR), 10 translation unrelated

(TU), within each of these above conditions , there will be equal numbers of

word pairs in each direction (Hindi-Kannada and Kannada-Hindi). To

counterbalance the language seen first by each participant, initial versions

of the experiment will be started with Hindi primes and later versions will

be started with Kannada primes. Two practice versions will be created using 5

word pairs. Results

and discussion: This section of the study will

be discussed later. REFERENCES: -Chen,H.C.,&Ng,M.L.(1989). Semantic facilitation nad

translation priming effects in Chinese-English bilinguals.Memeory and cognition,17,454-462. -Frenck,C.,&Pynte,J(1987). Semantic representation and

surface forms: a look at across language priming in bilinguals.Journal of Psycholinguistic Research,16,383-396 -Kiran S.& Lebel

K.(2007).Crosslinguistic semantic and translation priming in normal bilingual

individuals and bilingual aphasia.Clinical Linguistics &

Phonetics,21,277-303. --Poter,M.c.,So,K-F.,Von

Eckardt,B.,&Feldman,L.B.(1984). Lexical and conceptual representation in

beginning and proficient bilinguals. Journal

of verbal learning and verbal Behavior,23,23-48. Enhancing Students Writing Ability through Task Oriented

Responses to Listening Exercises: The Case of Pre-University Students in Iran

@Mahan

Attar and *S.S.Chopra @

Research student, Department of English, University o Pune, Pune-India. [Ministry

of Education, Hamedan District, Hamedan, Iran] E. Mail: attarm@yahoo.com *

University of Pune, Pune, India. E.

Mail: silloochopra@hotmail.com Writing

skill as one of the crucial aspects of communication is an obstacle for many

students. It is a complex process which requires attention to spelling ,

punctuation ,choice of words , sentence structure and a number of other

aspects . Some methodologists such as Celce -

Murcia (1991), have suggested the task-oriented response to listening

exercises in order to involve the learners in language learning, more

communicatively. According to Celce Murcia, there are two basic types of

students responses in listening exercises: 1) The question-oriented response

model. 2) The task -oriented response model. In question-oriented response

model students are asked to listen to an oral text, then answer a series

of factual comprehension questions on the content. In task -oriented

response model students make use of the information provided in the

spoken text, not as an end in itself but as a resource to use. This paper looks at pre-university

EFL learners in Iran and describes a research project which involved the

implementation of task oriented vs. question oriented responses to listening

exercises, designed to enhance students writing ability. Quantitative analysis performed on

the data suggests that the task oriented responses to listening exercises is

more effective than question oriented responses in promoting writing ability

of Iranian students. Data

N = Number of students

SD = Standard Deviation M = Mean T

= tobserved Table 1 The data derived from writing Pre test

Experimental group 25 44.9 12.6

0.29 Control group 25 43.85 12.55

Table 2 The data derived from writing Pre test

Experimental group 25 67.9 9.2

3.52 Control group 25 54.65 16.35

References Bahns, J.,

(1995). Theres More to Listening than Meets the Ear (respective review

article.) System 23(3):531-547 Canale M, Swain M.

Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching

and testing. Applied Linguistics (1980) 1(1):147.[Medline] Celce_Murcia , M.

(1991). Teaching English as a second or Foreign Language. 2nd

ed. California: Heinle and Heinle Co. Hymes D.

On communicative competence in J. B. In: SociolinguisticsPride,

Holmes J, eds. (1972) Harmondsworth: Penguin Lynch,T

.(1996).Communication in the language classroom. Oxford : Oxford University

Press. Nunan,D. (1989). Designing tasks for the communicative

classroom. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. Wilkins, D. (1976). Notional syllabuses. Oxford: Oxford

University Press. Phonological, Grammatical and Lexical Interference in

Adult Multilingual Subjects

Avanthi.

N & Abhishek. B.P & Deepa M.S. J.S.S. Institute of Speech and Hearing, Ooty Road, Mysore E. Mail: avanthi.niranjan@gmail.co; abhishek.bp@gmail.com;

deepalibra@gmail.com INTRODUCTION: Bilingualism

is defined as using or knowing more

than one language (can be more than two languages); so every bilingual person

is also multilingual, but the contrary is not necessarily true.. Language

interference is the alternative use by bilinguals of two or more languages in

the same conversation. Language interference is a linguistic practice

constrained by grammatical principles and shaped by environmental, social and

personal influences including age, length of time in a country, educational

background and social networks. The ability to switch linguistic codes,

particularly within single utterances requires a great deal of linguistic

competence. Interference of L1 on L2 occurs

in many components levels like phonological, lexical, grammatical.

Researchers argue that transfer is governed by learners perceptions about

what is transferable and by their stage of development in L2 learning. In

learning a target language, learners construct their own interim rules. AIM: To analyze the different types

of language interference (Phonological, Grammatical and Lexical) in multi

lingual adult speakers. METHOD: The

method was designed to uncover something of the complexity of language use in

a particular sample of language learners and so it had an explicit

descriptive purpose. 20 multilingual subjects were considered in the age range

of 21- 22 years of age. Among which 10 subjects were native Kannada speakers

and the other 10 subjects were non native Kannada speakers (Malayalam,

English and Kannada). 3 tasks

were considered Conversation, Narration and Picture Description. All

the three tasks were carried out in Kannada for both the groups (Native &

Non Native Speakers). Analysis was done for content and

complexity of language. The

data were transcribed verbatim, with verification for accuracy. To prepare

the transcribed data for analysis, repetitions, false starts and irrelevant

speech were deleted. The basic unit for segmenting the data was the T unit,

defined as one independent clause plus the dependent modifiers of that

clause. The narrative discourse tasks in the

study were analyzed in terms of sentential grammar, discourse grammar and

subjective quality. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: Analysis was done in 2 steps, analysis of content and

analysis of complexity. The analysis of content was

grouped under 3 measures, Phonological, Grammatical and Lexical. The analysis

of complexity was done by using T unit based analysis. To depict relationship

between the scores of native and non native Kannada speakers, paired

comparison t test was carried out for Narration and Picture Description

tasks. There was highly significant statistical difference between the two

groups considered, in terms of number of T units, number of Clauses / T unit,

number of words/clause, number of words/ T unit, number of Clauses, number of

Irrelevant clauses and number of words/ irrelevant clauses. The statistical

analysis indicated that difference was found in all the measures considered. The results are indicative of, the content and

complexity seen in the non native speakers is distinctively different from

the native speakers. And the interference is explained in the content part of

the study and the phrase length, compleixity of utterance which is the

reflect of the language proficiency is explained in terms of the T units. CONCLUSION: The study aimed at assessing the qualitative and

quantitative differences in the non native speakers of the language, their

proficiency of language and the different types of influence or transfer of

the dominant language to the non native language. The results also indicate

that there will be considerable influence or borrowing of features from a

language that is learnt earlier or used more excessively in ones social

context. In the present study, the

phonological, grammatical and lexical interference were studied. Further the

study can be extended by studying the influence of both L1 and L2 on L3 separately, analysing stress, rhythm,

intonation of the non native language can be done objectively and can be

compared with the native language, and studying more complex structures of grammar

of non native language. REFERENCES: Sima Paribakht. T., December (2005). The Influence of

First Language Lexicalization on Second Language Lexical Inferencing : A

study of Farsi Speaking Learners of English as a Foreign Language. Language Learning, 55:4, 701-748. Baljit Bhela, 1999. Native language interference in learning a

second language: Exploratory case studies of native language interference

with target language usage. International

Education Journal, Vol 1, No 1. Ellis, R. (1994). Factors in the Incidental Acquisition of Second

Language Vocabulary from Oral Input: A review essay. Applied Language

Learning, 5(1), 1-32. Frederika Holmes (1999). Cross-language interference in lexical

decision. Department of phonetics and

linguistics, Vol. 12 (2), 380-398. Faerch, C. &

Kasper, G. 1983, Plans and strategies in foreign language communication,

in Strategies in Interlanguage Communication, ed. C.

Faerch and G. Kasper, Longman, London. Poulisse, N. (1993). A

Theoritical account of Lexical Communication Strategies. The bilingual lexicon. Vol. 32, 157 189. Ecke and

Herwig (2001). Linguistic transfer and the use of context by Spanish

English bilinguals. Applied

Psycholinguistics, 18, 431 452. Yu, L.

(1996a). The role of crosslinguistic lexical similarity in the use of motion

verbs in English by Chinese and Japanese learners. Canadian Modern Language Review, 53(1), 190 218. Comparative Study of

Nagpuri

SUNIL

BARAIK Deptt. Of Tribal & Regional Languages of Jharkhand,

Ranchi University, Ranchi E.

Mail: s_baraik_in@yahoo.com Nagpuri is the Mother-tongue of ChikBaraik as well as 9

other tribes of Jharkhand. In this state many ancient tribes like Munda,

Oraon, Kharia, Chik Baraik and the total of 32 tribes dwell together

peacefully, all from different language groups (Austro Asiatic, Dravidian and

Indo Aryan). It is also the pidgin of Jharkhand. Almost all the tribal people

speak Sadani with some local variation. It is used by a large section of

tribal as well as non-tribal population either as a Mother tongue or as

lingua franca. There are different views regarding the origin and status of

Nagpuri. According to the Encyclopedia Mundarica, Sadri is the language of

Sadans It is also used as a Mother-tongue among some Munda, Oraon and Kharia

families residing in some parts of Simdega, Gumla, Lohardaga, Hazaribagh,

Ranchi and Khunti Districts. Apart from Jharkhand, Nagpuri is also spoken in Assam, West Bengal, Orissa,

Chhatisgarh and Bhutan where the people of Jharkhand migrated to earn their

living. In those places this language is also known as Sadri, Sadani, Gawari,

Nagpuri, Nagpuria and even Jharkhandy language. It is observed that almost

all the Oraons know this language. It is said that Oraons were banned of

using their Mother-tongue (ie; kurukh) in Chotanagpur by the kings. Hence

they were forced to adopt Nagpuri as their mode of communication because it

was the (Rajbhasha) official language of Chotanagpur at that time. Though the Oraons adopted this language as means of

communication, they also mixed some other tribal as well as Hindi words.

Nagpuri spoken by the Chik Baraiks is pure and is very much distinct from the

others. Nagpuri spoken by Chik Baraik tribe and Oraon tribe can very easily

be differentiated. My paper will be based on the comparative study of Nagpuri

spoken by Chik Baraiks and Oraons of Jharkhand. A Comparative Study of

Reduplication in Gujarati and Telugu

Asma

I. Barodawala & T. Sree Ganesh Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore This study aims at a comprehensive but at the same time

concise account

of the functions of reduplication across Gujarati and Telugu.

Reduplication is understood as

syntactic reduplication as defined by Wierzbicka (1986). While recognizing the origins of

reduplication in discourse, clausal and intraclausal repetition, universally

used pragmatic

devices, are excluded from this study. Likewise,

reduplication involving full

copies will be at the center of the analysis while partially reduplicated forms are considered

to be variants

eroded from fully reduplicated ones. Complete

Reduplication: GUJ: ઉભા ઉભા /ʊbʰa ʊbʰa/ standing

standing TEL: నిల్చుని నిల్చుని /niltʃuni niltʃuni/ standing

standing Partial

Reduplication: GUJ: રમત ગમત /rəmət

gəmət/ playing

and things like that TEL: ఇల్లుగిల్లు /illʊ gillʊ/ house and things like that Although reduplication can be

argued to constitute the least marked morphological

process (Couto 2000). The second

and perhaps more important

goal of this paper is to unearth the patterning of

reduplication in Gujarati and

Telugu. It is argued that in spite of the universality of reduplication,

substrate influence plays a crucial role

in determining the exact functions of reduplication. This

hypothesis is corroborated by my

findings from the study of the partly overlapping area of ideophones (Bartens

2000) which will be discussed as

a speacial category of reduplicated items in some of the creoles

under survey. Naming Deficits in

Bilingual Aphasia

Ridhima

Batra & Pallavi Malik & Shyamala K.C All India Institute of Speech and Hearing, Manasagangotri,

Mysore 06 E.

Mail: canif_ridhima@yahoo.com; charuthecharm@yahoo.co.in;

shyamalakc@yahoo.com INTRODUCTION Naming calls into play multiple levels

of processing. When used in conjunction with other basic tasks, it is usually

possible to determine whether the principal cause of naming deficits are

perceptual, semantic, or language output impairments. Naming of a visual

stimulus such as an object or picture begins with early visual processing and

recognition. The process of confrontation naming requires the formation of a

perceptual representation of the object. It requires access to some sort of

semantic representation to specify the concept that will then be tagged with

the correct verbal label. Bilingualism is an intriguing

phenomenon and has been defined variously by different authors. According to

Fabbro (1999) people who speak and understand two or more languages and

dialects are referred to as bi/multilinguals. Aphasia in a multilingual can

lead to different language deficits in the languages known and is called as

bi/multilingual aphasia. Naming deficits in aphasia are

seen as retrieval failures which take different forms, depending upon the

stage at which the breakdown occurs. A failure to retrieve the target lemma

results either in selection of another lemma that has a similar semantic

description i.e., semantic paraphasia; or a failure to retrieve a words

phonological description i.e., phonological paraphasia in which the word

sounds like the correct word but sounds are substituted, added or rearranged;

or a neologistic paraphasia with a production of a non-sense word. Paraphasias are common in aphasia and can help

differentiate fluent from non-fluent aphasia. AIM: To examine naming deficits in bilingual aphasics and

highlight the variation/correlation of these across languages. METHODOLOGY SUBJECTS:

6 Kannada-English Bilingual aphasic subjects were taken for the study. All

the participants were males. SUBJECT SELECTION CRITERIA: v Types of aphasia: Both fluent and non-fluent aphasic

syndromes were considered which was decided on the basis of clinical

observation and WAB-K (Kertesz & Poole, 1982) findings. Three fluent (2

anomic and 1 Wernickes) and three non-fluent (2 Brocas and 1 Transcortical

motor) aphasics were taken for the study. v Age range: 25-50

years. v All subjects were right handed which was determined using

self-report and information from significant others. v Subjects had Kannada as their mother tongue and had learnt

English as second language before the age of 10 years. v Subjects with any auditory or visual deficit were excluded

from the study. v Ethical considerations were met. PROCEDURE: Subjects

were seated comfortably. Then by casual talking, the subjects were made to

feel at ease and the procedure was explained before the evaluation and

recording began. The environment was made as distraction free as possible by

carrying out the procedure in a quiet room and by removal of any potential

visual distracters. The entire verbal interaction with the subjects was audio

recorded using Wavesurfer 6.0software. TEST ADMINISTERED: Naming

section of Western Aphasia Battery (Kertesz & Poole, 1982) was administered

in both Kannada and English language. ANALYSIS: The

naming section of WAB, for all the subjects in both the languages was

transcribed and analyzed for the presence of paraphasias (semantic,

phonological paraphasias and neologisms). Variation of paraphasias among the

fluent and non-fluent aphasic group and language specific errors in them were

identified and described. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS: Appropriate statistical measure was used for both

qualitative and quantitative analysis of the data. RESULTS

AND DISCUSSION: The type of naming deficits

exhibited by the fluent and non-fluent bilingual individuals with aphasia

will be discussed in detail, in the paper. REFERENCES Fabbro, F. (1990). The Neurolinguistics of Bilingualism-

An Introduction. London: Psychology Press. Kertesz, A., & Poole, E.

(1982). The aphasic quotient: The taxonomic approach to measurement of

aphasic disability. The Canadian Journal of Neurological sciences, 1, 7-16. Voicing patterns in Indian

English

Pratibha

Bhattacharya Department of Linguistics, University of Delhi, Delhi E.

Mail: thepratibha@yahoo.co.in The present study aims to understand and account for the

variability that exists with reference to voicing patterns as in the

following categories: a)

Plural

allomorphs (such as /s/ in [kQt-s] cats ;/z/

in [bQg-z] bags; /Iz/ in [mez-Iz] mazes) b)

Possessives

(such as black bucks legs in the sentence The black bucks legs are

broken) c)

3rd

person singular forms (such as loves in the sentence He loves

that girl) in English language in Delhi, India (commonly referred to as

Indian English). The paper also attempts to explore various possible

linguistic factors (acoustic phonetic, phonological and morphophonemic

factors) that are known to influence voicing. The

commonly assumed understanding of the three plural allomorphs of English (the

standard version) [s], [z] and [Iz] is that, these allomorphs

differentiated by the voicing or lack of it are induced by the final

consonant of the singular form of the noun as shown below. a) cat-s [kQt-s] Plural à [s] / C

---------------- # [- voice] [Plural] b) bag-s [bQg-z] Plural à [z]

/ C ------------------ # [+ voice] [Plural] c) maz-es [mezIz] Pluralà [Iz] / C ---------------- # [sibilants] [Plural] [palatals] The need for exploring the voicing pattern is to ascertain

to what extent English in India follows the same pedagogical rule as

described above. In the present context, it refers to the consonants in

Indian English and their ability to induce voicing in the adjacent

environments. It must be mentioned that Indian English is an umbrella term

that covers several varieties of English used as a second language in India.

These varieties are generally assumed to exhibit significant phonological

variations, stemming from various regional linguistic differences. Yet the results of the present study show

remarkable stability in voicing patterns and the contributory factors across

speakers in the sample. The study is based on data

comprising spontaneous speech and data obtained through reading tasks such as

word-lists, sentences and texts collected from a sample of 15 people born and

brought up in the city of North and North-West Delhi and who belonged to the

age group of 25 to 30 years. Resultative and Stative in

Bangla: How different?

Shiladitya

Bhattacharya University of Calcutta, Kolkata In Bangla we can have three different

semantic readings of Event, State and Result in passive constructions. In

Eventive Passive constructions there should be an agent who will be

performing the action where as in both Resultative and Stative readings there

is absence of an clearly indicated agent which makes them both different from

that of Eventive .Now when we look at the Resultative and the Stative

readings what we can mark as an essential difference between those is

that-the Resultatives have an indication to a result that is caused by an

action(which is done previously, by some agent may not be as clear as the Eventive reading

which has got a mandatory agent.).On the other hand in the Stative

interpretation of a sentence we find only the state of a thing/object/entity.

So in brief the distinction among the three can be put like this. Eventives

have a mandatory agent, Resultatives may or may not have an agent (i.e. the

action may be without a direct agent to say a voluntary or self agentive

action or it may have an agent which is not as clearly understandable as that

of an Eventive one) and the Statives express the state of thing/object

/entity (the presence or absence of the agent is not important). Our problem with Bangla is that

the two readings of Stative and Resultatives are sometimes phonetically

similar. In most of the cases when copula is dropped from the Resultatives

the two phonetic forms becomes similar and thus hard to distinguish. Examples

are given below. And it will be necessary to mention here that in case of

some verbs this difficulty arises. We are yet to make generalization that all

the verbs show the same phenomenon. In colloquial Bangla, the copula drop

from Resultatives is a common phenomenon and so the aim of this paper will be

to try to distinguish between these two readings at the conceptual level with

the help of some syntactic tests or devices. Bangla Passive

constructions have a clear distinction between its 1. Eventive and 2. Stative

and /or 3. Resultative readings. But, the real problem, as explained

above is to differentiate between its

(the Passive construction) Stative and Resultative readings as in most of the

cases their phonetic forms are similar. E.g.

Eventive: /drj(a khola holo/ Door open

happen-past The door was

opened. Resultative: / drj(a khola / Door open-present The door is

opened. Stative: / drj(a khola / ( /khola drj(a / the opened door is an Door open Adjectival Use) The opened

door. E.g.

Eventive: /dorja bondho holo/ Door close happen The door was

closed. Stative :

/bondho dorja/ Closed door Closed door Resultative: /bondho

kora dorja/ Closed do-inf. door Closed door. or /bondho dorja/ closed door Closed door. The

aim of this paper will be to try to identify any diagnostic procedure(s) that

can provide a clear distinction between the two readings (Resultative and

Stative) in Bangla. Reference: Landau, Idan. Unaccusatives, Resultatives and the

Richness of Lexical Representations.

Paper downloaded from http:// ocu.mit.edu/ visited on 31.10.2008 The Indo-Portuguese Creole of Diu: participant, alien

or observer of the Indian Linguistic Area?

Hugo

Canelas Cardoso Universiteit van Amsterdam, THE NETHERLANDS E.

Mail: hugoccardoso@gmail.com The

Indo-Portuguese Creole spoken in Diu (U. T. Daman, Diu, Dadra and

Nagar-Haveli), like most high-contact varieties across the world, establishes

important typological links with the various languages which were involved in

its formation and/or with which it coexists. In the specific case of Diu

Indo-Portuguese (henceforth DIP), the early days of contact, in the early

16th-century, involved Kathiawadi Gujarati and Portuguese. However, it is

likely that other codes also contributed to the initial `feature pool'

(Mufwene 2001), including possibly previously restructured varieties of

Portuguese, and neighbouring Indian laguages. In highly multilingual India,

examples of extreme linguistic convergence through contact are hardly

uncommon (recall the well-known case of Kupwar village, described in Gumperz

& Wilson 1971) but, unlike most such cases, the formation of the

Indo-Portuguese Creoles did not involve strictly languages which

traditionally participate of the Indian Language Area (henceforth ILA). It is

my purpose to ascertain to what extent the admixture observed in DIP has

brought it into the realm of the ILA by investigating its (non-)conformance with

the defining or salient typological characteristics identified for the ILA

(Emeneau 1956, Masica 1976, Subbarao 2008). This study reveals that DIP aligns with its primary

ancestor languages (Gujarati and Portuguese) in ways that are often difficult

to predict, and also that it is very difficult to try and rank the influence

of one language with respect to the other. A systematic comparison shows

that, alongside its links with Gujarati (e.g. case assignment) and Middle

Portuguese (e.g. basic word order), the (modern variety of the) Creole

diverges from both other domains (e.g. the relative absence of inflectional

morphology) - which raises important questions concerning the process of

creolization, on the one hand, and the exact composition of the initial

`feature pool', on the other. References Emeneau, Murray B. 1956. India as a linguistic area. Language 32:3-16. Gumperz, John J. & Robert Wilson. 1971.

Convergence and creolization: A case from the Indo-Aryan/Dravidian border. In

Dell Hymes (ed.), Pidginization and creolization of languages.

London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 151-67. Masica,

Colin P. 1976. Defining a linguistic area: South Asia. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press. Mufwene,

Salikoko. S. 2001. The ecology of language evolution. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press. Revised Receptive Expressive Emergent Language Scales for

Kannada Speaking Children

Deepa

M.S., Madhu K, Harshan K & Suhas J.S.S. Institute of Speech and Hearing, Ooty Road, Mysore E.

Mail: deepalibra@gmail.com INTRODUCTION : Language development is a process that starts early in

human life, when a person begins to acquire language by learning it as it is

spoken and by mimicry. Child language development move from simplicity to complex.

Many tests have been developed for language in toddlers. Even though they

have been developed many decades back, they are still in practice in almost

all clinics in India. But the tests need to be revised because children are

observed to be developing many skills at very early age. AIM: To revise the REELS (Receptive

Expressive Emergent Language Scales) for children exposed to Kannada

language. METHOD: 720 children from all over

Karnataka with age range of 0-3yrs served as subjects for the study. The

children were divided into different age ranges 0-3 months to 33-36months.

The milestones in REELS both receptive and expressive skills were numbered

and used for the study as questionnaire which was administered to the

parents/caregivers. The responses were tabulated and analyzed. RESULT AND DISCUSSION: The results collected from all

three regions were gathered and standard deviation was calculated. To

rearrange milestones 80%criteria was used. If 80% of children are passing a

particular milestone that milestone stone is shifted to the lower age groups.

There was highly significant difference seen in 1st to 3rd

year but the milestones did not differ significantly in the lower age group

that is less than 1 year CONCLUSION: Results revealed that there was significant

difference seen in second to third year of life than in first year, both in

reception and expression. So the revised REELS contain the skills which have

been shifted to lower age group using 80% criteria. But the scale need to be

administered to clinical population and has to be checked for validity. Also

there is unequal number of skills in each age range, equal number of skills

has to be distributed and revised further. REFERENCES American academy of

pediatrics.,(1980). Caring for your

baby and young child: Cambridge UK. 213-224. Anerew, N.M., Freckerit, Z.,(2007)

Association between media viewing and

language development in children under 2 year age: Washington DC: Author. 92-100. Anisfeld, M.,(1979) Interpreting "imitative" responses in early infancy. Science, 214-215. Aslin, R.N., & Pisoni, D.B.,(1980) "Effects

of early linguistic experience on speech discrimination by infants: " Child

Development, 107-112. Bzoch, K., League, R. and Brown, L. (2002) REELS (receptive expressive emergent language scale) 1st

and 3 rd edition. Caroline,

B. (1998), Typical Speech Developmen: Washington DC: Author..240-253 Elisabeth, H., Yousef, E. (2000) Developing a

Language Screening Test for Arabic-Speaking Children. Harlekar, G.(1987)

3-Dimensional language test Johnson, C.J., & Anglin, J.M. (1995) Qualitative

developments in the contents and form of childrens definitions. JSHR,

28:612-629. Moog, J.S., and Geers, A.V. 1975. Scales of early communicatin skills (SECS) Nippold, M.A. (1998) Later language development. The

school age and adolescent year.

Cambridge UK. 219-240 Natson, R .(1985) Towards a theory of definitions, Journal of child language development,

12:181-197. Prathanef, B., Pongajanyakul, A., (1998) International journal of language &

communication disorders.41, 214-120 Reed, V. (1992) Introduction

to child language disorders (1995). Springer publishers. 345-356. Relationship between Symbolic Play, Language and Cognition

in Typically Developing Kannada Speaking Children

Devika.M.R,

Navitha U & Dr. Sapna N. All India Institute of Speech and Hearing, Manasagangotri,

Mysore 06 E. Mail: dvkspdevika@gmail.com; naviudew@gmail.com Introduction:

Play is defined as any voluntary activity engaged for the enjoyment it gives

without consideration of the end result (Piaget, 1962). Play serves as a

platform for social interaction (including co-operating with each other and

working together towards a goal, turn taking, decision making, problem

solving etc.), emotional, motor, cognitive and language development. It

combines action, language and thought (Tassoni & Hucker, 2005). Symbolic play is one of the surface

manifestations of symbolization. Symbolization is the fundamental process of

cognitive development. Play develops

throughout a child's life, and it evolves from simple physical manipulation

of objects to sophisticated and planned sequenced play. The ability to play

symbolically emerges during the second year of life. For many

years, language pathologists, psychologists and other researchers have tried

to discover evidence for the linkage between language, play and

cognition. In the west, many studies carried out on typically developing children

evidenced mixed results, some which confirmed the fact that there is a

correlation between symbolic play and language(McCune-Nicolich, 1981, Ogura

1991).Lyytenin, Laakso(1997) and Chik Hsia Yu Kitty (2000), others which

showed no significant relationship between symbolic play and language,

particularly mean length of utterances (MLU) Shore, (O-Connell and Bates

1991) In addition, there are limited studies which investigated the

relationship between play, language and cognition especially in the Indian

context. Hence it becomes necessary to study the correlation between these

three skills in typically developing children. Objectives: Is there any relationship between

symbolic play, cognition and language development in typically developing

children? Does play correspond with the language comprehension and/or

expression? Method: Subjects: The sample included 10 typically

developing Kannada children in two different age groups 24 to 30 months and

30-36 months. Subjects were mainly recruited through nursery, kindergartens.

Each group consisted of 5 subjects with close to equal number of males and

females in each group. The children included in the study had no history of medical problems, emotional, behavioural or

sensory disturbances. Each child was administered Three-Dimensional Language

Acquisition Test (3D-LAT) (Geetha

Harlekhar, 1986) to

assess their receptive, expressive and cognitive skills. Assessment checklist

for play skills (Swapna, Jayaram, Prema, Geetha, in progress) was

administered to get the age equivalent play scores. Procedure: To study the symbolic play behavior, two sessions of play

were organized in which all the children participated in two types of play

situations viz. free play and structured play. The play sessions were video

recorded. Structured

play: Each child was presented with

four sets of thematically related toys, one set at a time, and they were

allowed to interact with them for approximately 5 minutes each. The sets

included several standard toys which would facilitate symbolic play and

either a stick or a block as an item to be transformed. Free

play: Each child was presented toys such

as kitchen set,furniture set,doll,quilt .truck,tool kit etc which were spread

in the vicinity of the child. The child was

invited to play with the toys. The mother was seated in the room but

was asked not to intervene in the childs play. This session lasted for

approximately 10 minutes. The symbolic play behaviours such as functional play,

sequential play and verbalized elaborate play were studied The qualitative

differences in symbolic play and the frequency of symbolic play in the two

different age groups were analyzed. The play behaviors observed during the

free and structured play was used to rate the assessment checklist for play

skills. This was done in addition to the information obtained about the play

behaviour though parental interviews. Based on the observations made the age

equivalent scores for play were calculated. During free play, the toy

preferences also were noted in terms of the toys that are reached out first

and the duration of play with a specific toy. Gender differences were also

studied. Results: Appropriate

statistical analysis was applied to investigate the differences with respect

to the symbolic play patterns, the relation between symbolic play, language

and cognitive development, toy preference among both the groups and the

difference in genders. The findings indicated that there was a positive relationship

between the subjects' chronological age and play, language and cognitive age.

The data supported the hypothesis that symbolic play correlates with language

and cognitive development. The results will be discussed in detail with

respect to variables such as toy preferences and gender differences. The

developmental differences between various play behaviors are also discussed. Conclusion: The study of child language to describe and analyze

spontaneous production of spoken language, with a cognitive and pragmatic

framework contributes not only a more accurate understanding of normal play

and language development, but also has an efficient clinical value. This

suggests that play and language reflect the different underlying mental

capacities in the young child. Such information would contribute to the

assessment and diagnosis of children with communication difficulties. References: Bates, E., Benigni, L., Bretherton. I.,Camaioni, L.,&

Volterra, V.(1979).The emergence of

symbols:cognition and communcation in infancy. New York:Academic Press Chick Hsia Yu Kitty (2000)

Correlation between symbolic play and language in normal developing

Cantonese speaking children. Dissertation submitted as a part of partial

fulfillment for the bachelor of science, speech and hearing sciences.

University of Honk kong . Geetha

Harlekhar (1986) Three dimensional language acquisition test (3D-LAT)

unpublished dissertation, speech and

hearing. Mysore university. McCune-Nicolich,

L. (1981). Toward symbolic play functioning: Structure of early pretend games

and potential parallels with language. Child

Development, 52, 785- 797. Piaget, J. (1962). Play,

dreams, and imitation in childhood. New York: Norton and Company Swapna, Jayaram, Prema, Geetha, (in progress), an ARF

project undertaken at AIISH, Mysore Tassoni, P., & Hucker, K.

(2005). Planning play and the early

years. Heinemann ELDP Data Collection: Some

Baram Experiences

Dubi

Nanda Dhakal, TR Kansakar, YP Yadava, KP Chalise, BR Prasain & Krishna Paudel Central Department of Linguistics, Tribhuvan University,

Kathmandu, Nepal E.

Mail: dndhakal@yahoo.com We have been documenting the Baram language, a language of

Tibeto-Burman language spoken in the western Nepal since May 2007. This

programme has been supported by ELDP (Endangered Languages Documentation

Programme), School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London and hosted

by Central Department of Linguistics, Tribhuvan University, Nepal. The

sociolinguistic setting of the language reveals that this is a seriously

endangered language when we assess the degree of language endangerment by

means of the criteria set by UNESCO (2005). There are about three dozens of

fluent language speakers, and only about a dozen of fluent language speakers

can actually contribute good texts for language documentation. The language is not used for natural

communication. The task of collecting data is more challenging because the

Baram community does not use it in natural setting. We follow Himmelmann (1998) in the beginning to collect

the data which are more varied and functional. He explains that the

communicative events can be placed in a continuum. On the one extreme that

are spontaneous expressions like exclamation, or the expressions to show pain

and anger and on the other extreme there are expressions which are well

planned like the language used in ritual and so on. All sorts of human

communication is possible with different kinds of interactions between these

two extremes. Unfortunately, in the Baram language we did not find the use of

language in both of these extremes. The language is neither used at natural

setting nor is it used in the rituals. Taking Himmelmann (1998) as a departing point, we expanded

the inventory of communicative events covering several areas. We follow Lupke

(2005) while expanding the inventory. In order to have very restricted

structure of the language we follow Leech and Jan Svartvik (1994). They help

us get the paradigm for writing a sketch grammar. We also follow Franchetto

(2006:189) to collect data on ethnographic topics like celebration of

festivals, cultural occasions and so on. We may summarize the inventory of communicative events and

genres which are (1) Exclamative (cries, signs of surprise, joys etc (2)

Directive (ordering, permission, telling, vocative etc) (3) Conversational

(conversation, chat, discussion, interview, songs etc. (4) Monological

(historical, personal), myths, speeches and routines etc. (5) Rituals

(ritual, birth and death ceremony) etc. Due to the restricted use of language, we are unable to

have data for the genres like language of rituals, formulaic expressions like

greetings and leave taking and so on.

We followed very rigorous method of data collection for this process

and finally succeed in collecting the representative corpus. Due to very limited language use, we also used stimuli

like documentary films, clips of songs, photographs, and some questions typed

on the laptop etc. We hope the methodology can be used while working with

severely endangered languages. In this paper, we are discussing various strategies used

in data collection. Aside from this, we also talk about different language

speakers and which area they can contribute. We find that some speakers can

contribute to the narrative texts whereas some others are useful in myths and

rituals. We have collected about 65 hours of texts including audio and video

recordings. Most of these files were recorded at our field office in Gorkha

which is located in the western part of Nepal. We suggest the following recommendations for field workers

based on our field work: (1) Make an inventory of different genres, communicative

events and ethnographic topics. This

help you capture diverse sessions with different uses of the language. (2)

Work with different speakers. One may be good at narrating stories, another

at giving instruction and another perhaps at data elicitations for making

paradigms.(3) Make a proper analysis of data you have collected before you

record texts for hours! You will be surprised to see that the linguistic

contents of the speaker who speaks for a long time may be worthless! (4) Make

your sessions of moderate length. If they are very long, i.e. for an hour,

they may be difficult to handle in some computer softwares like ELAN,

TOOLBOX, AUDACITY when these files are edited and annotated. (5) Record some sessions

which are directly related to grammar, i.e. 'conditional clause', 'purposive

clause', etc. This helps you get the language in use while writing grammar.

(6) The language speakers should be properly trained before recording the

sessions if you intend to have specific topics and structures recorded. References: Abbi, Anvita. 2001. A Manual of

Linguistic Fieldwork and Structures of Indian Languages. Lincolm

Handbooks on Linguistics, No.17. Munchen: Lincom Europa. Franchetto, Bruna. 2006.

Ethnography in language documentation. Essentials of Language

Documentation. (Ed) Gippert, Jost, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann and Ulrike

Mosel. Berlin and New York; Mouton de Gruyter. Grinvald, Colette. 2003. Speakers

and documentation of endangered language. 53-72. Language Documentation

and Description Vol. 1. (Ed) Peter K. Austin. Endangered Language

Project. Himmelmann, Nikolaus. 1998.

Documentary and Descriptive Linguistics. Linguistics 36:161-95. Leech, Geoffrey and Jan Svartvik.

1994. A Communicative Grammar of English. Singapore: ELBS. Lupke, Fiederike. 2005. Small is

beautiful: contributions of field-based corpora to different linguistic

disciplines, illustrated by Jalonke. 75-105. Language Documentation and

Description Vol 3. (Ed) Peter K. Austin. London: Endangered Language

Project. Samarin, William J.1967. Field

Linguistics: A Guided to Fieldwork. New York: Holt Rinehart and sinston,

Inc. Yavada, Yogendra P.1998. Lexicography

in Nepal. Kathmandu: Royal Nepal Academy.

UNESCO. 2005."Safeguarding of

the Endangered Languages: The Endangered Language Fund Newsletter, 7:1. Some Methodological Observations on Linguistic Fieldwork:

Case Studies from the Maharashtra Karnataka Border

*Arvind Jadhav &

#Nick Ward *Y C College

of Science, Karad. Distt. - Satara. Pin-415124 India (MS) #

University Of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW.

AUSTRALIA E. Mail:

lecturer.arvind@gmail.com; nwar3485@mail.usyd.edu.au Two

current case studies are used to illustrate some methodological considerations

in undertaking linguistic fieldwork. One is an investigation into the

language of the traditional Indian healing systems of Ayurveda and

Yog-therapy, as they are practiced in The

investigators have ample theoretical background and are in the process of

applying this theoretical knowledge to their fieldwork studies. Past

methodologies are discussed, and their applications to the present researchers

work are considered and reflected upon. Case

study 1: In this study recordings of consultations between Ayurvedic

practitioners and Yog-therapists, and their patients are used as a basis for

investigating metaphor and figurative language within the formal linguistic

frameworks of these traditional practices in Marathi. The data are collected

from the Case

study 2: Language convergence process occurring due to prolonged language

contact situation has been a topic of interest and intense enquiry in

Sociolinguistics. Other than prolonged language contact situation, language

convergence occurs due to immigration and in the case of tribal languages. In

General

issues of linguistic fieldwork methodology are identified (as articulated,

for example, in Eckert, 2000; Rajyashree, 1986; Milroy 1987), and strategies

for addressing these issues are discussed with specific reference to the

above case studies. Amongst these general issues and challenges are the

following: 1. Selection of the locality for the study. 2. Consideration of what type of language required for

recording (e.g. Spoken or written; casual conversation or a more structured

format like a ceremony or ritual). 3. Entering the communication network, and the

implications of the chosen method. 4. Consideration of what specific things are to be looked

at in the language (e.g. lexical items such as slang words or address forms;

syntactic structures; pragmatic strategies, etc.), and how to elicit the

required forms. 5. Legal and ethical implications such as consent and

voluntary participation of respondents. 6. Self involvement of the primary investigators, and

dependence on assistants for certain purposes. 7. Methodological tools to be used and their

standardization. 8. Representation of all social variables, and

consideration of which variables

are relevant. This paper will employ a multi-disciplinary approach to

make a meaningful contribution to the fields of linguistic methodology, and

Indian language studies. REFERENCES: Barrett,

Robert J, and Lucas, Rodney H. 1993. The Skulls

Are Cold, the House Is Hot: Interpreting Depths of Meaning in Iban Therapy.

Eckert,

Penelope. 2000. Linguistic Variation as

Social Practice. Gumperz,

J.J. and Wilson, Robert. 1971. Convergence and Creolization-A case from the

Indo-Aryan/ Dravidian border in Konitzer, M., Schemm, W.,

Freudenberg, N., and Fischer, G.C. 2002. Therapeutic interaction through metaphor: An

interactive approach to homeopathy. Semiotica.

141-1/4. pp.1-27. Lakoff,

George. 1990. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. Milroy,

Lesley. 1987 (2nd Ed). Language

and Social Networks. Pandit,

P.B.,1972. Bilinguals Grammar -Tamil Saurashtri Grammatical Convergence.

In Rajyashree, K.S. 1986. An

Ethnolinguistic Survey of Dharavi: A Slum in Lexical Organization in

Malayalam-English Bilinguals

Sweety

Joy, Meera Priya.C.S, Aiswarya Anand & Jayashree Shanbal J.S.S. Institute of Speech and Hearing, Ooty Road, Mysore E.

Mail: sweety.slp20@yahoo.com; meeracs_18@yahoo.co.in;

aiiisu_aiiisu@yahoo.co.in; jshanbal@gmail.com Introduction: Haugen, (1953) defined

bilinguals as individuals who are fluent in one language but who can produce

complete meaningful utterance in the other language. Since majority of world

population is comprised of bilinguals (De Bot, 1993), a host of studies on

bilinguals is documented in the recent past. The nature of bilingual lexical

organization is an enduring question in bilingual research (Snodgrass, 1984).

An attempt has been made to understand this with different models and

experiments by various researchers. Amongst these experiments, priming

studies have been one widely used method to understand processing

organization. Relationship between lexical organization of a bilingual

semantic, translation priming paradigm and picture naming tasks can be used

to evaluate lexical decision in bilinguals. Studies conducted till date, have

been mostly in alphabetic languages like English, which falls into the Latin

language family. Indian languages, on the other hand are considered syllabic

or semi-syllabic languages. Studies investigating priming patterns in Indian

English bilinguals (like Malayalam-English) are thus necessary to study the

nature of language processing and its representation in syllabic or

semi-syllabic (non-alphabetic languages). Aims of the study: Present study was designed with

the following objectives, 1. To investigate cross language priming (translation

and semantic) in normal M-E bilinguals adults at 250 millisecond stimulus

onset asynchrony (SOA), using a stimulus set designed for automatic

processing. a) prime presented in Malayalam , (L1) and the

target in English (L2) ; L1-L2 condition b) prime is presented in English (L2) and the

target in Malayalam ( L1);L2-L1 condition 2. To investigate cognitive flexibility using

picture naming task and thereby check the sensitivity of word association (Potter,1984) and

concept mediation model (Potter 1984),by comparing the reaction time taken

for picture naming task and L1-L2 translation task. Method: Subjects: Eighteen adults in the age

range of 17- 30 years, with Malayalam as mother tongue and English as second language,

participated in the study. Educational qualification with a minimum of 12

years of formal education was considered for subject selection. Subjects were

categorized as bilinguals or monolinguals based on ISLPR (International

Speech Language proficiency rating scale) (Wiley & Ingram, 1985) scores. Test Stimuli List 1: Translation equivalent word

pairs, semantically related word pairs, semantically unrelated word pair

forms the stimulus material for lexical decision task. Prime words would be

given in Malayalam and target was in English. List 2: Prime words would be given in

English and the target was in Malayalam. List 3: 10 categories of nouns with

each set of five pictures in series having four pictures from one lexical

category. A total of fifty pictures were chosen for the study. Instrument A Compaq 2374 model laptop with

DMDX software (Forster & Forster, 1999) was used for the experiment. Procedure Task 1: The experiments comprised of

two language conditions: Malayalam English and English to Malayalam,

consisting of 3 blocks the stimulus set in each block containing 63 word

targets ( 21 translation equivalent (TE, ) 21 related( R ) word , 21

unrelated (UR) prime target word pairs. The final list consisted of 126

word targets in both the language order. Prior to each experimental session

(i.e. for each individual subjects), the order of items with in each of this

block randomized and then the order of three blocks was randomized so as to

decrease the likelihood of extraneous serial effects such as practice or

fatigue. Stimulus presentation was controlled by DMDX software (Forster &

Forster, 1999). Subjects responded by pressing the key 1 (for a yes

response) and key 0 (for a no response) on the key board. Reaction times

(RTs) were recorded to the nearest millisecond and stored in the computer. Task 2: Series of pictures were shown

on the computer screen .Subjects was instructed to name the picture as early

as possible in their native language. The verbal responses were recorded with

the help of a microphone connected to a computer. Recording and Scoring The reaction times in

milliseconds of all the critical targets were automatically recorded in

Microsoft excel by the software further data was analyzed using statistical

package for social science (SPSS-10.0) version software. Results and Discussion The results will be discussed

in light of the differences in lexical organization in bilinguals proposed

for bilinguals in the western population in comparison to the Indian population

following a different script structure. REFERENCE: Colthart., & Karanth,P.,(1984).Analysis of the

acquired disorders of reading in Kannada. Journal of All India Institute

of Speech and Hearing, 15, 65-71. De Bot, K. (1993). A Bilingual production model: Levelts

speaking model adapted. Applied Linguistics, 13, 1-24 Forster,J., & Forster,k.(1999).http://

www.u.arizona.edu/~ kforster /dmdx., retieved on 12/9/2008. Haugen, E. (1953). The analysis of linguistic borrowings. Language, 26,210-231 Potter, M.C., So, K.F., Von Eckhart, B., & Feldman,

L.B. (1984). Lexical and conceptual representation in beginning and proficient bilinguals. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 23, 23-38. Wylie., & Ingram, E.D.,

(1985). How native like? Measuring language proficiency in bilinguals. Journal of Applied Linguistics, XI

(2), 47-64 Temporality in Bengali: A

Syntacto-Semantic Framework

Samir

Karmakar Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT, Kanpur E.

Mail: samirk@iitk.ac.in The syntactic pattern of Bengali verb morphology shows the

following structure: 1. V-aspect-tensei-personi

Here, I would show how the syntactic structure corresponds

to the temporally significant semantic aspects, such as temporal ordering, viewpoints,

lexical aspect, and argument structure, in Bengali. Following Reichenbach (1947), the information about the

temporal order could be captured in terms of speech time (= S), and reference

time (= R), whereas the relation between reference time and event time (= E) gives an idea about

the viewpoints. These two relations are popularly known as first and second referencing, respectively. On the other hand, the

information of lexical aspect is a consequence of aktionsarten.

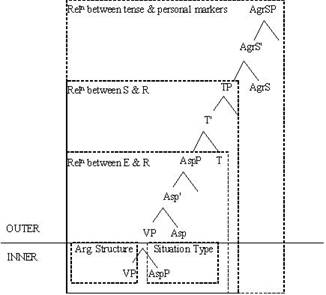

Fig 1: Syntacto-Semantic Frame of Temporality in Bengali The information pertinent to temporal order and viewpoint constitutes

the outer layer of the frame; whereas aktionsarten

along with the argument structure

constitutes the inner layer of the frame (Verkuyl 1989, 1993). Inner layer of

the frame represents lexical aspect in terms of duration, and telic

features. Outer layer is mainly concerned with (i) the relation between

speech time and reference time, in terms of precedence and overlap,

and (ii) the relation between reference time and event time, to construct

either perfective or imperfective viewpoints. Arche (2006) has shown how these

semantic notions could be incorporated into a syntactic framework, simply by

assuming tense and aspect to be dyadic

predicate relations. The framework, which I have outlined here differs in

certain respects from that of Arches one, mainly due to the language

specific peculiarities of Bengali. The adverbial adjunct modifies the lexical aspect of a

sentence either as state, or process, or event, thus coercing the verb semantics. Such modification is

proposed to be dealt with in the inner layer of the frame, under the node of

aspect.

The sentence from Bengali above

has two readings: (i) the act of singing was accomplished in fifteen minutes (accomplishment); and, (ii) the act of

singing was started in fifteen minutes

(inception). However, in case of

(2b), no such problem arises. It simply means, the act singing had been

performed for fifteen minutes.

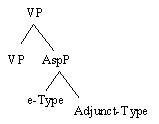

As a consequence the inner layer of aspect needs to be

further decomposed in the following way:

Fig 2: Further Specification of VP-internal Aspectualities Integration of syntax and semantics is crucial, since it

shows how the semantics of tense, aspect (both grammatical and lexical), and

the adjunct interact with each other, while construing the temporal

interpretation of a sentence that takes into cognizance the discourse level

contextualities. References: Arche, M.J. (2006). Individuals in

Time: Tense, Aspect and the Individual/Stage Distinction, Amsterdam: John

Benjamin Publishing Co. Verkuyl, H. (1989). Aspectual

Classes and Aspectual Composition. Linguistics and Philosophy, Vol. 12,

39-94. Verkuyl, H (1993). The Theory of

Aspectuality: The Interaction between Temporal and Atemporal Structures,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reichenbach, H. (1947). Elements

of Symbolic Logic. New York: The Free Press. Gilchrist's 'A Grammar of

Hindoostanee Language': Some Colonial and Contemporary Imprints

Santosh

Kumar Deptt. Of Linguistics, University of Delhi, Delhi E.

Mail: santoshk.du@gmail.com The contextual and textual analysis of a piece of grammar has always

been an interesting and challenging area of inquiry. This paper examines

Gilchrists A Grammar of Hindoostanee

Language with the aim to show that often grammar-writing can be seen to

provide a framework to keep in circulation the imperialist project

(Bhattacharya 2004) The

history of writing grammars shows that grammars are written for specific linguistic reasons such as to provide a principled

description of a particular language; to be a basis for

language pedagogy; to compare one grammar with another for typological,

historical, and aerial characteristics or for pedagogically oriented

contrastive analysis, and to test linguistic theories (Ferguson, 1978).

However, there are some non-linguistic reasons such as culture, religion,

ecology, aesthetics, pragmatism, etc. that influence the practice of writing grammar, wittingly or otherwise

(Scharfe, 1977). The latter perspective provides a significant site for raising questions of

representation, power and historicity. John

Borthwick Gilchrists A Grammar of Hindoostanee language or part third of volume

first of a system of Hindoostanee

philology (Calcutta, Chronicle Press, 1796) is one of the earliest

grammars written on the Hindustani language. This well-studied text can

however be seen as representative of the colonial language policies put in

place by the British to serve their needs in addition to its being

representative of the British attitudes towards Indian vernaculars in general

and Hindustani in particular.

Notwithstanding problematic such as these in a purportedly scientific

activity like grammar writing, this paper also presents comparative evidence

to show that the contemporary mindset is not without blemish when it comes to

pursuing an imperialist agenda through academic writing. Reference: Bhattacharya, Tanmoy. 2004. Hand me my slippers and other such phrases as a part of grammar:

Pettigrews Tangkhul Naga Grammar. Paper presented at the 26th

AICL Meeting, NEHU. Bhatia, Tej K. 1987. A History of the Hindi Grammatical

Tradition: Hindi-Hindustani Grammar, Grammarians, History and Problems.

Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill. Ferguson, C.A. 1978. Multilingualism

as object of linguistic description. In Kachru, Braj B. ed.

Linguistics in the Seventies: Directions and Prospects. Department of Linguistics,

Urbana, University of Illinois. Gilchrist, J.B. 1796. A Grammar of the Hindoostanee language or

Part third of volume first of a system of Hindoostanee philology. Calcutta:

Chronicle Press. Scharfe, Hartmut, 1977. Grammatical Literature. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. Suleri, S. 1992. The Rhetoric of English India. Chicago: The University of Chicago

Press. The Biolinguistic Diversity Index of India

Ritesh

Kumar Centre for Linguistics, SLL&CS, Jawaharlal Nehru

University, New Delhi E.

Mail: riteshkrjnu@gmail.com In recent times there has grown a strong hypothesis which asserts

that the biological, cultural and linguistic diversity of a country or a

region are positively correlated. These three diversities are together termed

as 'biocultural diversity'. Thus, biocultural diversity unifies the diversity

of life in all of its manifestations: biological, cultural, and linguistic.

These are interrelated and have coevolved within a complex socio-ecological

adaptive system. There are three basic assumptions underlying the concept of

biocultural diversity:

The cumulative effect of all these local interlinkages,

interdependencies and interaction between the humans and the environment

implies that at the global level, biodiversity and cultural diversity are

also interlinked and interdependent. Thus, it has significant implications

for the conservation of both the diversities. Recent global cross-mappings of

the distributions of biodiversity and linguistic diversity (taken as a proxy

for cultural diversity) have revealed significant geographic overlaps between

the two diversities, especially in the tropics. Moreover, they have shown a

strong coincidence between biologically and linguistically megadiverse

countries. It has been noted that generally the social factors

combine with the geographic and climatic factors leading to a higher or lower

diversity. For example, geography and climate of a particular area affects

its carrying capacity and access to resources for human use. Ease of access

to abundant resources seems to favour localized boundary formation and

diversification of larger numbers of small human societies and languages.

Where resources are scarce, the necessity to have access to a larger

territory to meet subsistence needs favours smaller numbers of widely

distributed populations and languages. The development of complex societies

and large-scale economies, which tend to spread and expand beyond their

borders, also correlates with a lowering of both linguistic and biological

diversity. Moreover, there is a significant overlap between the location of

threatened ecosystems and threatened languages. On the other hand, low

population density, at least in tropical areas, seems to correlate positively

with high biocultural diversity. It has been argued that similar forces are currently

posing a danger to both the linguistic and the biological diversity on Earth.

And the preservation of both the diversities is extremely necessary for

similar reasons. While biodiversity provides us the resources of Nature on

which we can fall back for our sustenance and better living, linguistic

diversity gives us the vast pool of knowledge from which we can draw upon to

make our life better. The knowledge of biodiversity and how it can be used is

encoded in thousands of so-called tribal, backward and insignificant languages.

Once these languages are lost, we lose this vast pool of knowledge in the

form of traditional knowledge, from which we could have learnt a lot. One of the biggest obstacles in this nascent field of biocultural

(or, biolinguistic, for my purpose) diversity is the lack of a proper

methodology and a good database. Since these diversities are best expressed

in terms of figures and numbers, we need to have some kind of mathematical

and statistical index for representing this integrated notion of

biolinguistic diversity and then by studying the fluctuations in this index

over a period of time, we can gauge the extent to which these diversities are

under threat. Obviously after that the qualitative analysis regarding the

causes and the possible solutions to

this threat is necessary. But in order to get the qualitative analysis to the

point and exact, we need to know the exact proportion and extent of the

threat. Harmon and Loh calculated the 'Index of Biocultural

Diversity' (IBCD) at the global-level (they calculated the index for each

country and then compared them). However the problem with their methodology

was that it could not be used for smaller areas or intra-country calculation

of index. So it required some modification. In this paper I have calculated

the IBLD (Index of Biolinguistic Diversity) of India using a similar

methodology. However I have introduced some modifications. Instead of taking